No matter how carefully you prepare your US patent application, the odds are very good that you will receive at least one Office action rejecting the claims. After all, there is a lot of prior art out there. In fact, if your patent is allowed without any Office actions, the odds are also very good that your claims were too narrow; reducing the value of your invention, and filing for reissue may be your only option to regain that lost claim scope.

So, an Office action can sometimes be a good thing, as it gives you the opportunity to maximize your claim scope given the constraints of the best references available before your patent issues. It also can keep your competitors in the dark as to what your final claims will be as you can tweak them to fit your most current needs if done properly.

But responding to an Office action can also be a minefield of problems if not handled carefully. While there is plenty of advice out there concerning the legal and technical do’s and don’ts when responding to an Office action, I want to talk about avoiding a frequent mistake more related to the human nature side of the response.

One of the most common errors I see made when responding to an Office action is failing to fully understand how and why the examiner has interpreted the claims “so badly”. Often we immediately see that the reference is different and just make that argument. But this can be a mistake.

The examiner is not our enemy, but a negotiator whose job it is to enforce the novelty requirements. The examiner is also well educated, smart, and very specialized in his/her field. Examiners know and understand the technology. Sure, I've seen some bogus rejections and there are some well publicized questionable patents that do slip through the cracks in the system, but by and large the examiners do a pretty good job.

When a reference used in a rejection has a purpose or structure different than that of your application, it doesn't mean that the examiner doesn't understand your invention. They usually do. It often just means that the claims can be interpreted differently from what you intended, and you are merely being shown a different interpretation which is just as valid as your own.

Usually a client and/or the agent preparing the response is quite familiar with the invention, which is a very good thing if amending claims, but this familiarity also tends to make us interpret claims to fit our own understanding of the invention. This relative lack of objectivity can prevent us from seeing what the claims really say. As the proverb goes, “we see what we want to see”.

To help overcome this "we see what we want to see" predisposition, some clients or colleagues quite successfully make up claim charts individually comparing each limitation of the claim with the reference. While often useful for me too, this method has a drawback in that claim charts are still limited to words, and words are still subject to the same semantic meanings we inherently seek. So one trick I've used for years to help conquer this predisposition is to put away the application, from my desk and from my mind, to get a pen and a blank sheet of paper, and to draw a crude picture of the claim, one limitation at a time, exactly the way that it is described in the claim.

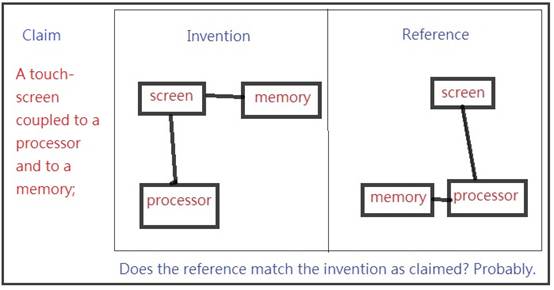

For example, if the claim says "A capacitive touch screen".... draw a labeled rectangle on the page, "coupled to a processor".... draw a processor rectangle somewhere else at random on the page and a line connecting the two rectangles, “and to a memory”… draw the memory rectangle and the connection to the touch screen. You get the idea.

It is very important while drawing this claim picture to NOT think about the invention. Do not think about relative sizes or locations of elements. Forget the textbook circuits you learned at school. Forget your experiences. Draw like a child would do if you read them the claims. Only draw what the words in the claims specifically say, nothing more, and nothing less. Your drawing should not look like the invention; it should only reflect the claims.

When you are finished, take the rejection back out and compare it with your drawing (See diagram 1), and only the drawing. It can be surprising what a crude visual representation of the claims can do as far as your understanding of what the examiner is saying and why he/she is saying it. Often the result is your sudden realization that the examiner, unfortunately, is right. After all, claims tend to be fairly broad and there is a lot of prior art out there. It's not too difficult for the examiner specializing in the field to come up with combinations of references that may suggest these broad limitations.

Diagram 1: Compare the rejection with your drawing

But a realization of how and why the examiner is correct can also be your salvation. Now that you know what he/she is thinking and the crude drawing has shown you what you are really claiming, you are in a better position to make the necessary arguments or changes. A patent only requires a single novel feature. If your drawing already shows a novel feature, point it out to the examiner. If it doesn't, work only with your picture. Find a way to tweak your drawing or add something new to your drawing that gives it a novel feature. Only then amend your claim accordingly.

Doing this offers another advantage too. The examiner will know that instead of you wanting to just argue with them, you are really trying to understand and respond to what they are saying. This often leads to them listening more carefully to you. Any counselor will tell you that this kind of "I am listening to you and understand what you are saying" exchange is quite important in any successful resolution of differences. There is a lot of prior art out there, but thinking visually instead of only verbally can often help you better understand the examiner's point of view, and doing that can give you the edge in the negotiations. |